Abaqus Concrete structure Modeling Full Tutorial

If you are a researcher, student, university professor, or Engineer in the company in the field of civil engineering, Abaqus concrete structure modeling package in simulating concrete and structural Engineering is the best selection.

All facets of concern modeling and simulation are covered in this full tutorial. The package includes 19 workshops on topics such as concrete, beam-column structures, composites, steel rebars, Ultra-High-Performance-Fiber-Reinforcement Concrete columns, CFRP bars, hollow-core square reinforced concrete columns wrapped, damaged concrete beams, High Strength Concrete(HSC),ECC/Concrete Composite Beam-Column Joints, circular concrete-encased concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) stub columns, and etc.

You can see the syllabus and details of this workshop below or the drop-down menu on the right side of this product page.

It will guide you going from the basics up to complex simulation techniques. It is very fluid, and comprehensive and every single detail is explained.

It will guide you going from the basics up to complex simulation techniques. It is very fluid, and comprehensive and every single detail is explained.

Every workshop goes straight to the point, without any worthless piece of content. You will learn what you need at every stage and you will be putting it into practice from the very first day.

Every workshop goes straight to the point, without any worthless piece of content. You will learn what you need at every stage and you will be putting it into practice from the very first day.

Most importantly, we support you as you learn in this course. You can contact our experts to ask your questions and enjoy our modelling and simulations step-by-step support.

Most importantly, we support you as you learn in this course. You can contact our experts to ask your questions and enjoy our modelling and simulations step-by-step support.

What are the exact contents of each video in this package?

It should be noted that this package includes only workshops; there is no lesson at the beginning of each workshop, contrary to our other main training packages.

This video training package contains more than 300 minutes of video tutorials. Click on the chapters of each lesson in the right section of this tab to know the details of the tips and issues presented in this very comprehensive and useful ABAQUS course package.

It would be useful to see Abaqus Documentation to understand how it would be hard to start an Abaqus simulation without any Abaqus tutorial.

Read More: Abaqus download edition | How to download Abaqus?

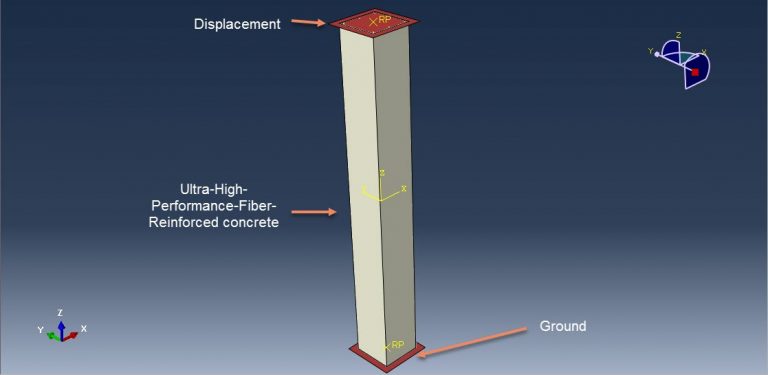

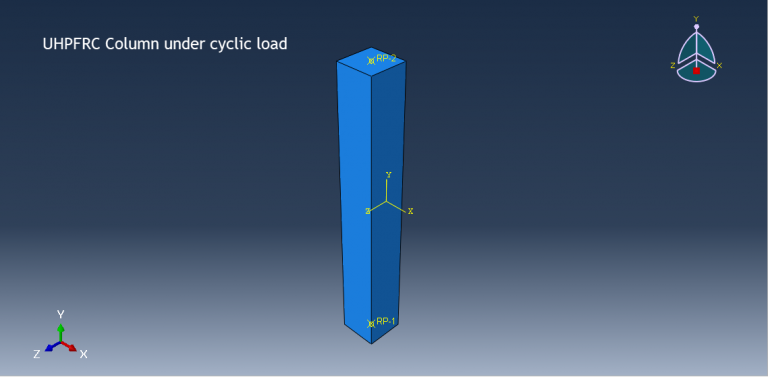

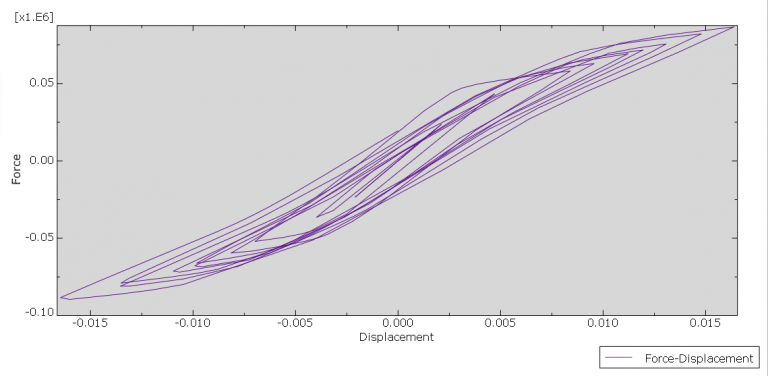

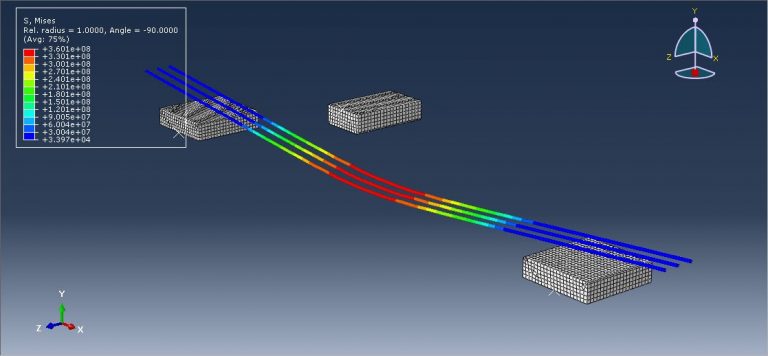

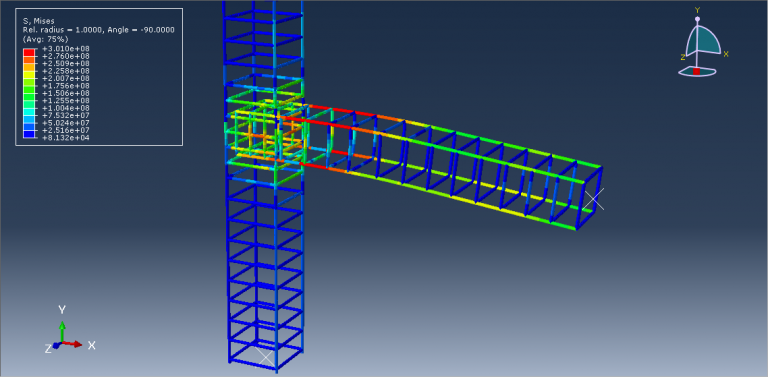

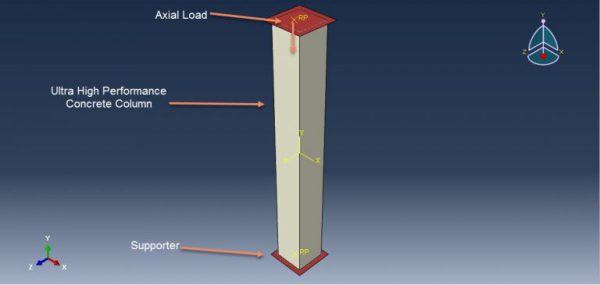

This workshop covers the simulation of cyclic loading on an Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (UHPFRC) column in Abaqus. The column is modeled as a three-dimensional solid structure.

UHPFRC is a specialized concrete made from Portland cement, reactive admixtures, fine aggregates, inert additives, superplasticizers, and surface-treated steel fibers. The optimized grading of its components results in a high packing density, providing exceptional strength, ductility, and durability. While high-strength cement-based materials typically fail suddenly after cracking, the addition of fibers delays the formation of interconnected microcracks and enhances the material’s toughness through fiber-matrix interactions. This behavior gives UHPFRC a pseudo-strain-hardening response post-cracking, followed by strain localization at peak load and a gradual loss of strength until failure. The material’s inelastic behavior—such as matrix cracking, fiber debonding, and slip—contributes to its high ductility and energy absorption capacity.

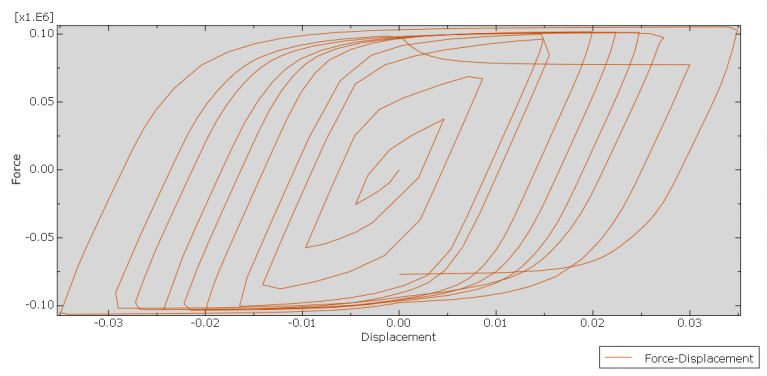

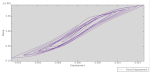

In this workshop, the Concrete Damaged Plasticity model is used to represent UHPFRC under cyclic loading. Material properties are derived from reference studies. The analysis is performed using a general static step with convergence modifications. To generate the hysteresis diagram, displacement and reaction force data are collected. The cyclic load is applied to the top surface of the column following a predefined amplitude, while the bottom surface is fixed. A fine mesh is necessary to ensure accurate results.

After the simulation, results such as stress distribution, strain evolution, and the hysteresis diagram will be available.

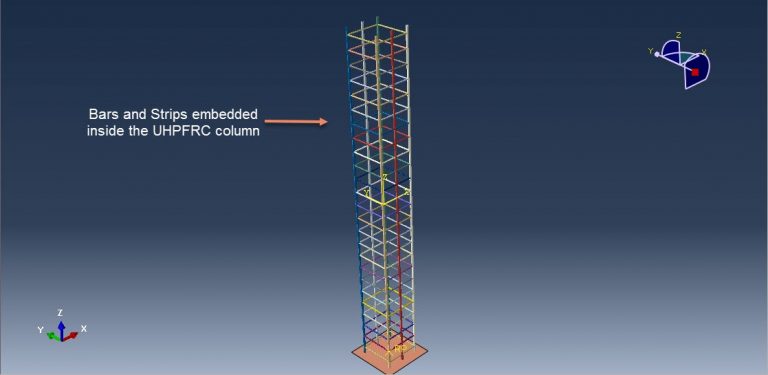

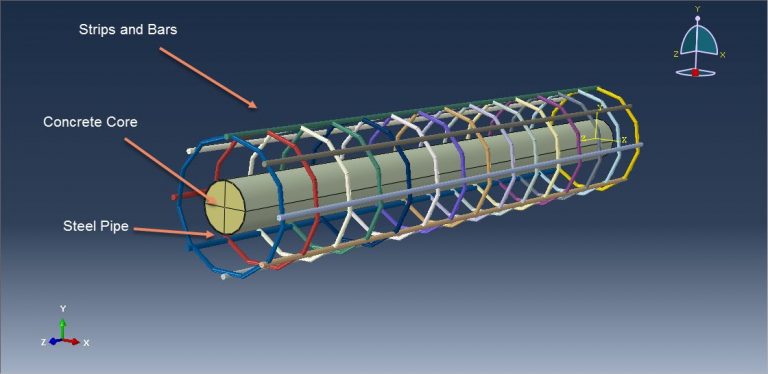

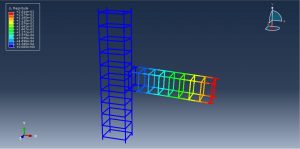

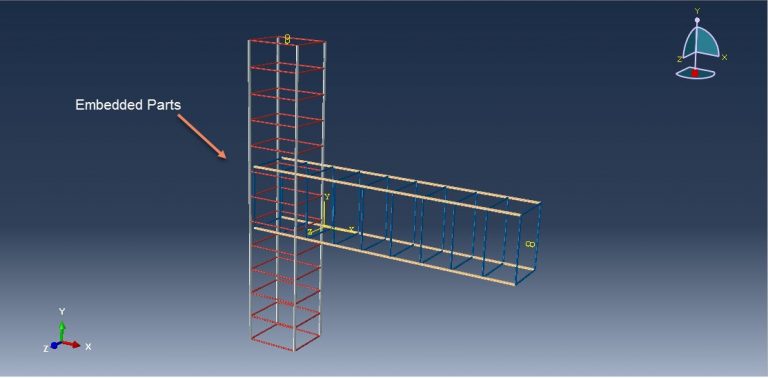

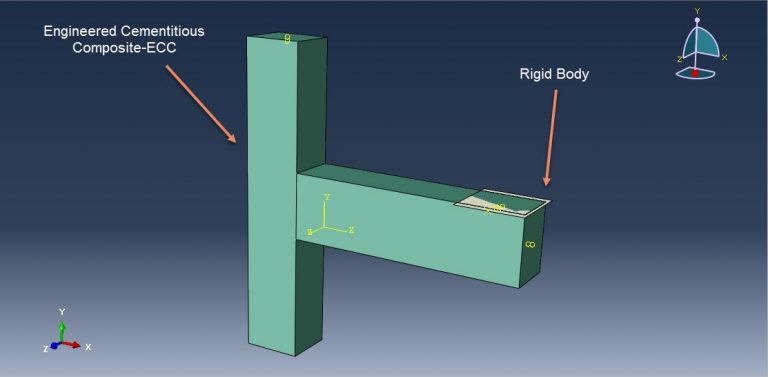

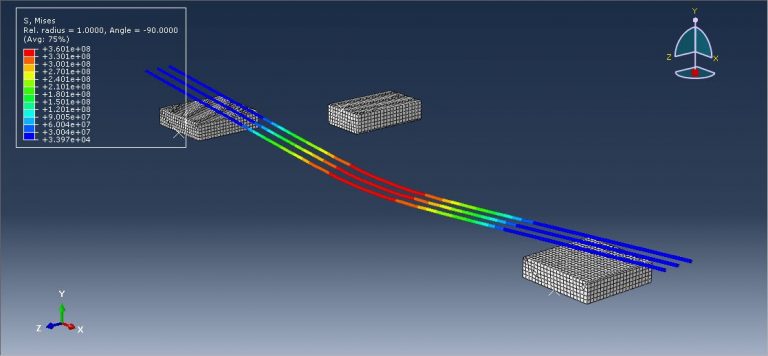

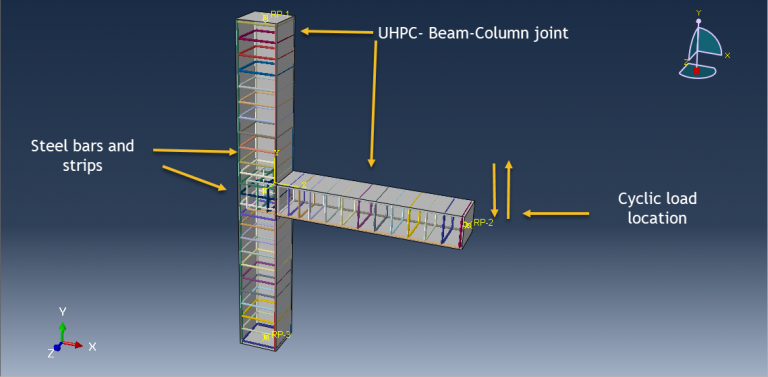

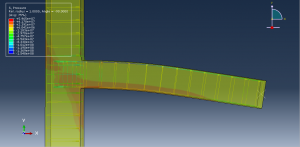

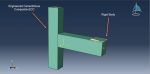

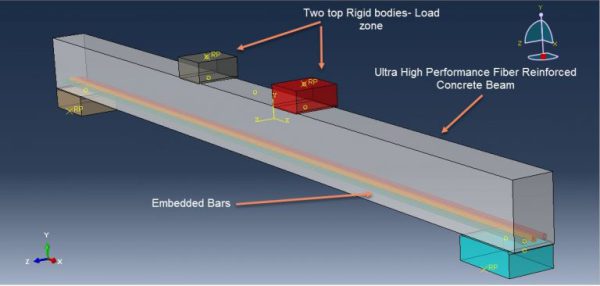

This workshop examines the simulation of an Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) beam-column joint subjected to cyclic loading in Abaqus. The UHPC beam-column joint is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, while the steel bars and strips are represented as three-dimensional wire parts.

UHPC is an advanced concrete technology known for its exceptional strength in compression and tension, high ductility, and durability. In this study, UHPC material properties are used to model the beam-column behavior under cyclic loading. The Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model requires separate compression and tensile data, while the elastic-plastic material model is applied to the steel bars and strips.

To simulate cyclic loading, a general step with adjustments in the divergence model is used, and the necessary outputs are requested to generate the hysteresis diagram in the visualization. The embedded region constraint is applied to ensure proper interaction between the steel bars, strips, and the concrete host. Fixed boundary conditions are assigned to both the top and bottom surfaces of the column, while cyclic displacement is applied to the free end of the beam following a predefined protocol. A fine mesh is essential to obtain accurate results.

After the simulation, results such as stress, strain, displacement, and the hysteresis diagram will be available.

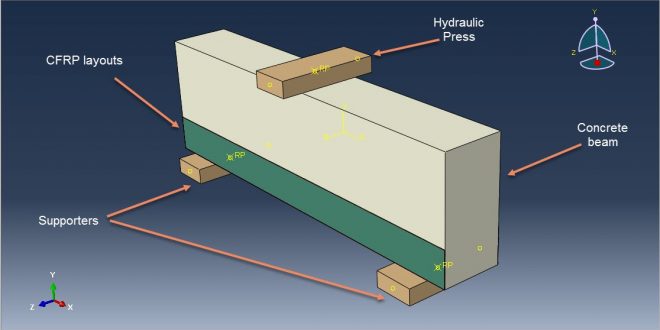

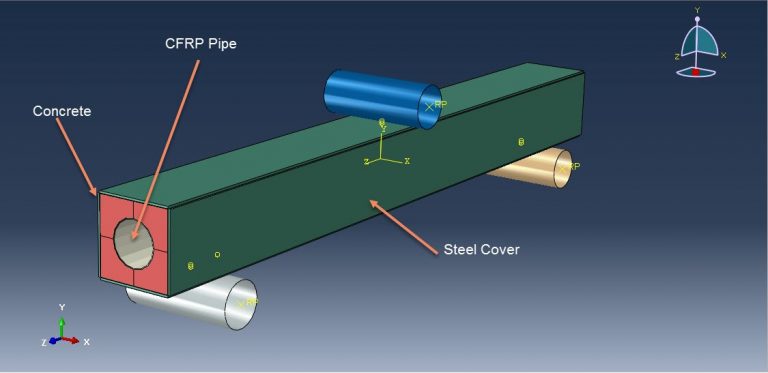

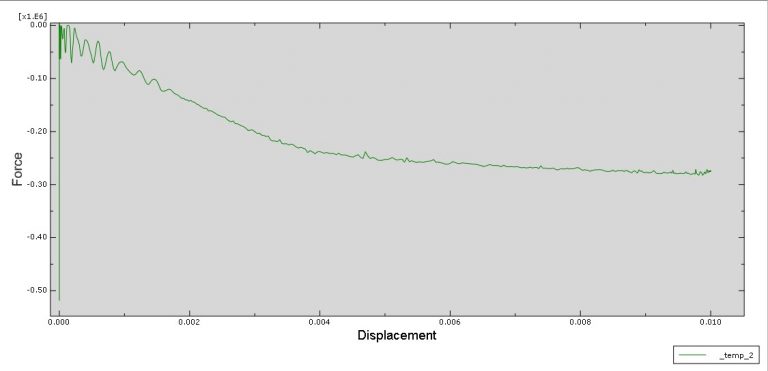

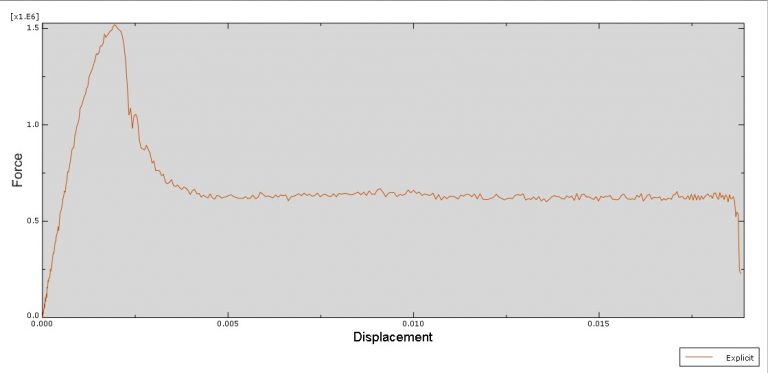

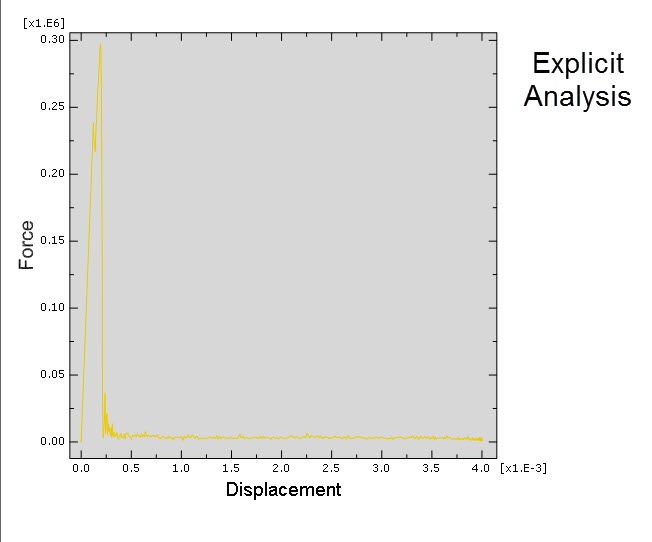

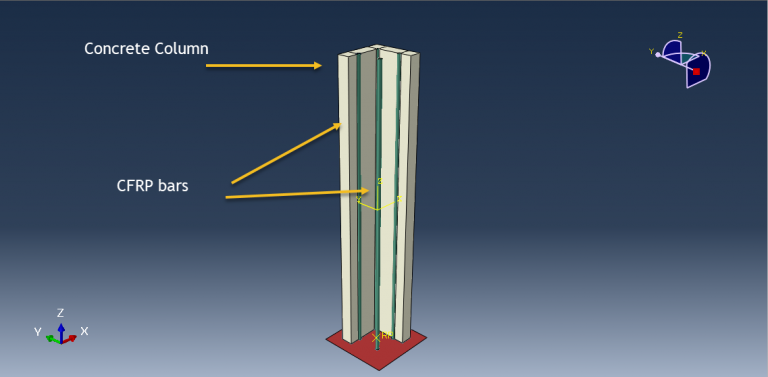

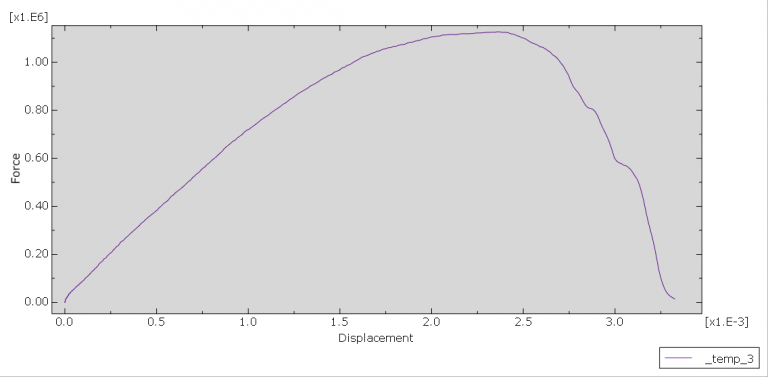

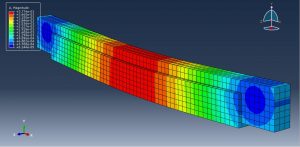

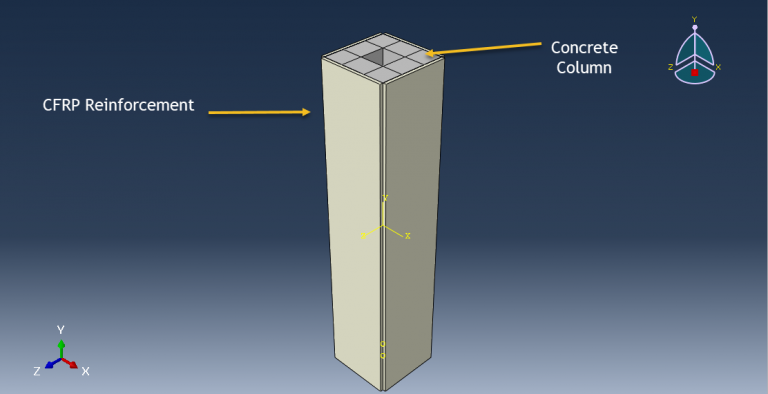

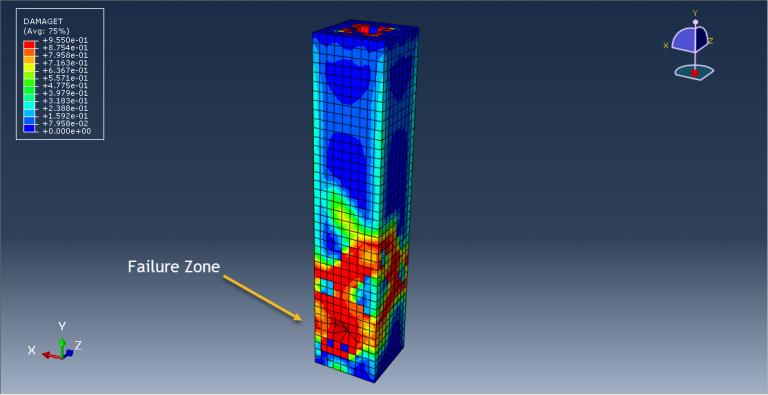

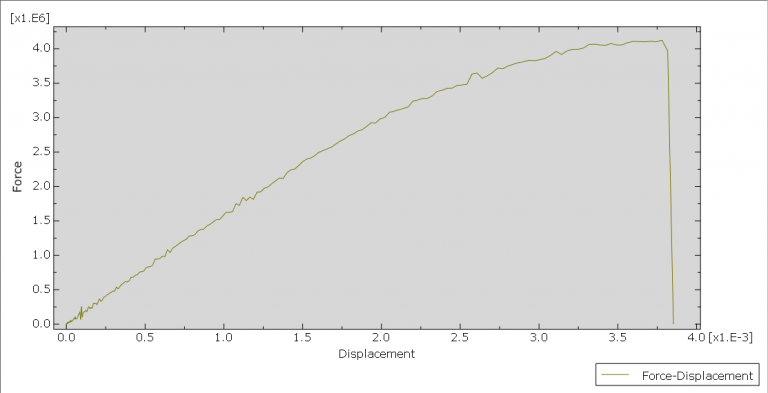

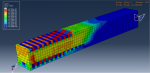

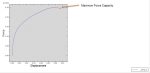

This workshop focuses on the dynamic compression test simulation of a concrete column reinforced with CFRP bars in Abaqus. The concrete column and CFRP bars are both modeled as three-dimensional solid parts, while two rigid bodies—a supporter and a hydraulic jack—are included in the setup.

To accurately represent the behavior of concrete and account for its damage, the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model is used. This continuum-based plasticity model considers tensile cracking and compressive crushing as the primary failure mechanisms. The CFRP bars are modeled using an elastic engineering constants approach.

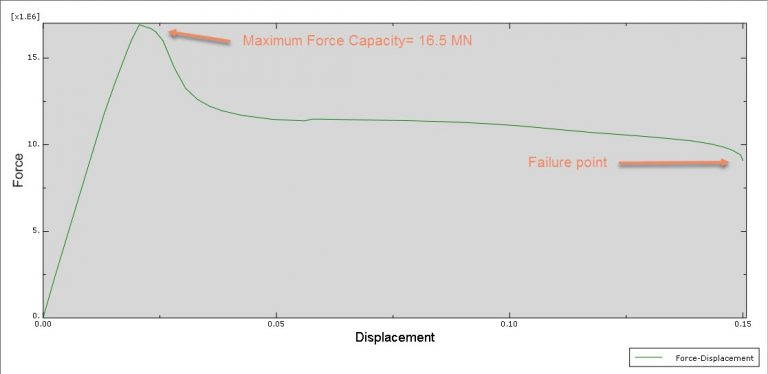

A dynamic explicit step is employed to capture failure zones and determine the maximum force capacity of the column. The explicit solver is preferred over a static solver due to the significant convergence issues that occur in this type of analysis. A general contact algorithm is applied to manage all interactions within the contact domain, with friction defined as a contact property. The interaction between the CFRP bars and concrete is assumed to be ideal (perfect contact). Boundary conditions include a fixed constraint on the bottom rigid body, while displacement is applied to the top. A fine mesh is essential for achieving accurate results.

After completing the simulation, results such as stress distribution, plastic strain, tensile and compression damage, and the force-displacement diagram are available.

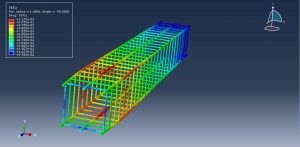

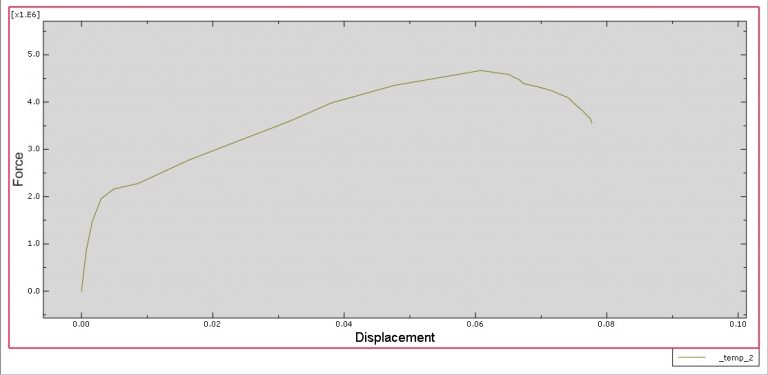

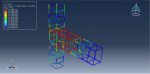

This workshop examines the simulation of hollow-core square reinforced concrete columns wrapped with CFRP under compression in Abaqus. The concrete column is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, while the CFRP wrap is represented as a three-dimensional shell part. The steel bars and strips are defined as three-dimensional wire parts, and a rigid shell body is included to apply the load.

Transverse FRP wrapping along the column’s axial direction is widely used, as it provides significant confinement pressure to the concrete core under compression. This reinforcement delays concrete crushing and longitudinal steel reinforcement buckling, enhancing both compressive strength and deformation capacity. Among hollow-core columns, those with circular openings demonstrate superior performance compared to those with square openings.

To model the concrete behavior under compression, the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model is applied. The steel reinforcement follows an elastic-plastic material model, while the CFRP wrap is defined using elastic lamina properties with Hashin’s damage criterion for failure prediction.

This workshop includes both static and dynamic simulations:

- In the static analysis, a general static step with modifications to the convergence model is used to prevent premature divergence. The steel bars and strips are embedded inside the concrete host, and perfect contact is assumed between the outer concrete surfaces and the CFRP wrap. The bottom of the column is fixed, and displacement loading is applied through the rigid part. Due to material failure and damage progression, the static simulation requires significant computation time and may be substituted with a dynamic analysis.

- In the dynamic analysis, a dynamic explicit step with mass scaling is used. This approach efficiently captures failure mechanisms, and the force-displacement diagram provides insights into structural response.

After running the simulations, results such as stress distribution, strain, damage evolution, failure patterns, and the force-displacement diagram are available.

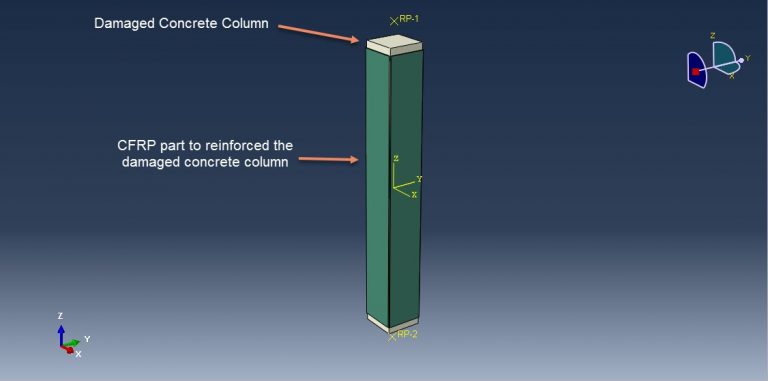

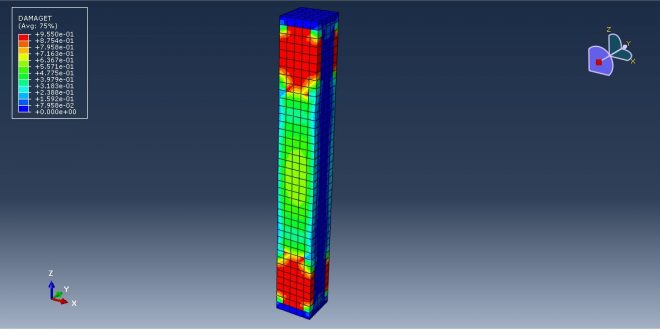

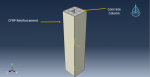

This workshop explores the axial compression simulation of a damaged concrete column with initial residual stress, reinforced with CFRP, in Abaqus. The concrete column is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, while the CFRP box is represented as a three-dimensional shell part. The analysis consists of two sequential simulations:

- First Simulation: The concrete column is subjected to axial loading, generating damage and residual stresses. These results are then recorded for use as initial conditions in the second simulation.

- Second Simulation: The CFRP box is introduced, covering the damaged areas of the column, and a new axial load is applied to evaluate the enhanced performance.

To model concrete behavior under axial loading, the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model is used, while the Hashin’s damage criterion defines the CFRP response. In the first simulation, two static steps are employed:

- In the first step, an axial load is applied to the column.

- In the second step, the load is deactivated to capture the residual stresses and damage state.

The bottom of the column is assigned a fixed boundary condition, while an axial load is applied to the top surface. The results from this simulation—stress, strain, tensile and compression damage—are then imported as initial conditions for the second simulation.

In the second simulation, the damaged column with residual stress is analyzed, now reinforced with the CFRP box to cover the damaged areas and enhance load capacity. A progressively higher axial load is applied until failure occurs, allowing for a comparison of performance before and after CFRP reinforcement.

Following the simulations, results from both analyses—such as stress distribution, strain, damage progression, and failure patterns—can be compared.

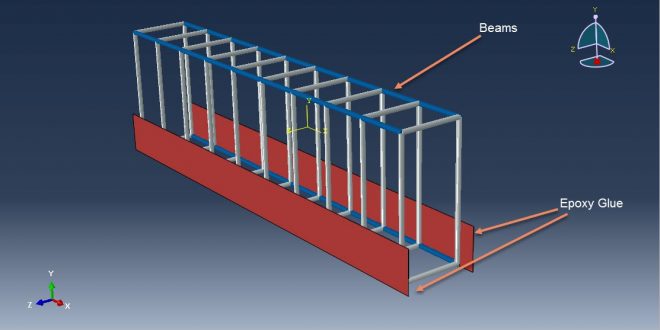

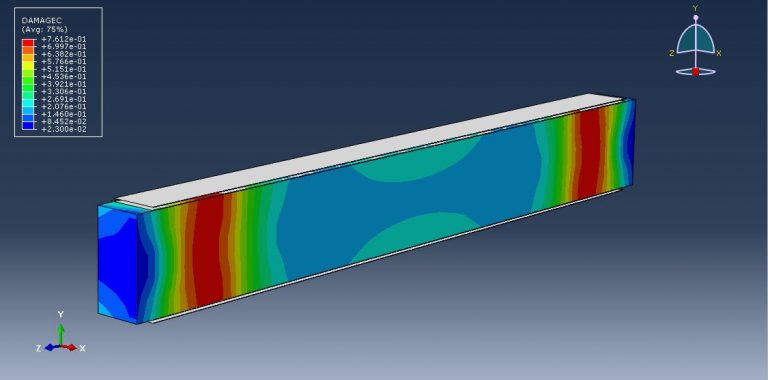

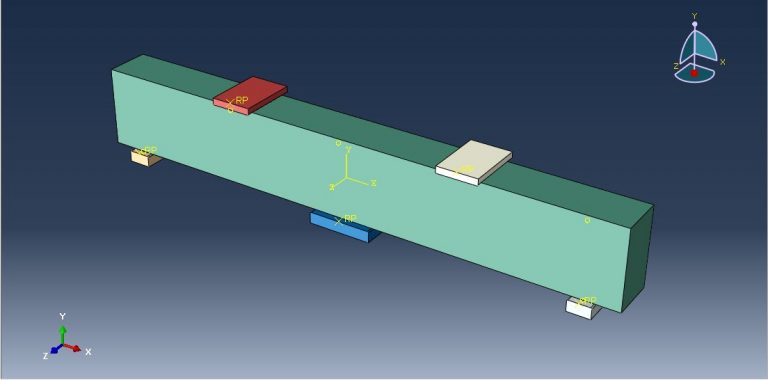

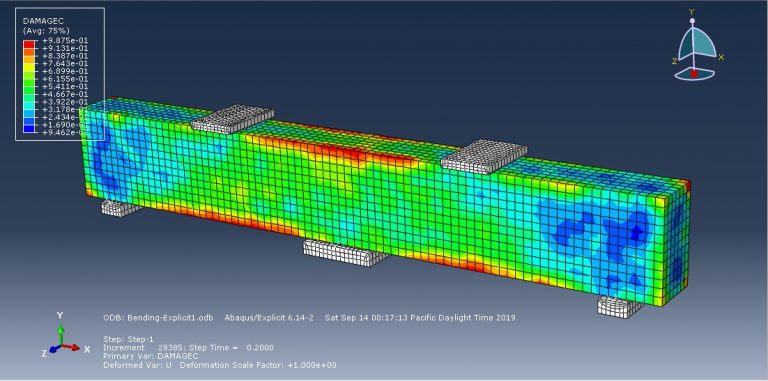

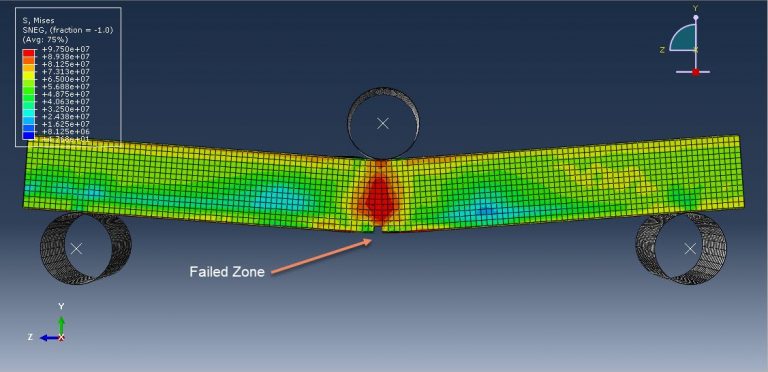

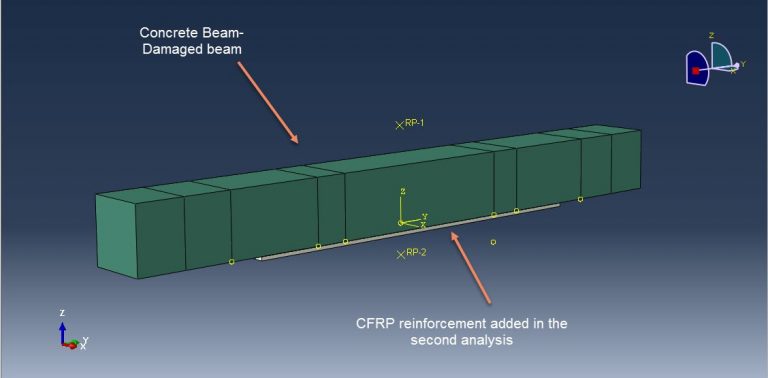

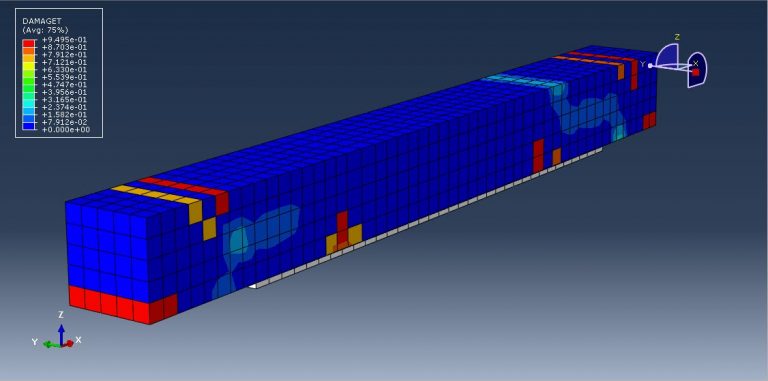

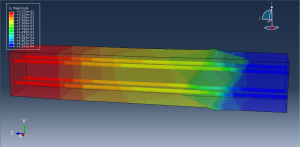

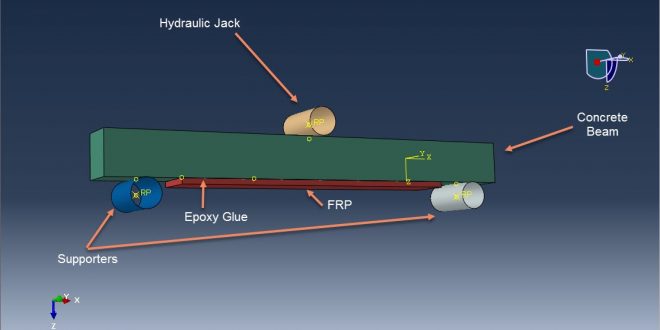

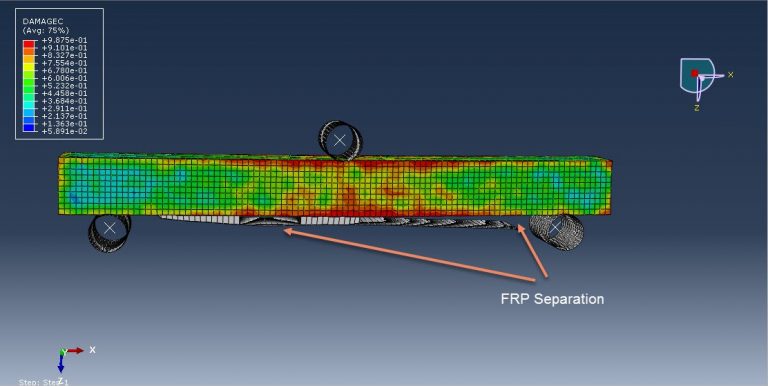

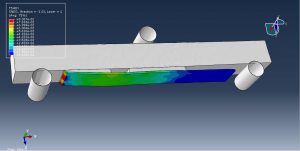

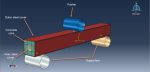

This workshop examines the simulation of a damaged concrete beam with initial residual stress, reinforced with a CFRP sheet under bending load in Abaqus. The concrete beam is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, while the CFRP sheet is represented as a three-dimensional shell part. The analysis consists of two sequential simulations:

- First Simulation: A four-point bending test is performed on the concrete beam to generate stress distribution and damage patterns. These results are then extracted and used as initial conditions for the second simulation.

- Second Simulation: The CFRP sheet is applied to the damaged areas of the beam, and the residual stress and damage from the first simulation are imported into the new analysis.

In the first simulation, a general static step with modified convergence settings is used. To ensure that data from this analysis is available for the second simulation, the output results must be saved as an output file. The bending load is applied at two zones of the beam, while boundary conditions are assigned at the beam’s ends. Once the simulation is complete, results such as stress, strain, tensile and compressive damage are obtained.

In the second simulation, the CFRP sheet is introduced to reinforce the damaged zones from the previous analysis. The residual stress and damage state from the first simulation are used as the initial condition for the beam. The CFRP reinforcement is expected to enhance the beam’s performance, allowing it to withstand the same or increased load more effectively.

After completing both simulations, results from each phase—including stress distribution, strain, damage evolution, and structural performance—can be analyzed and compared.

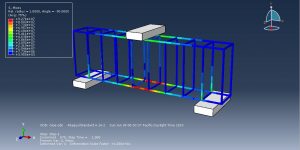

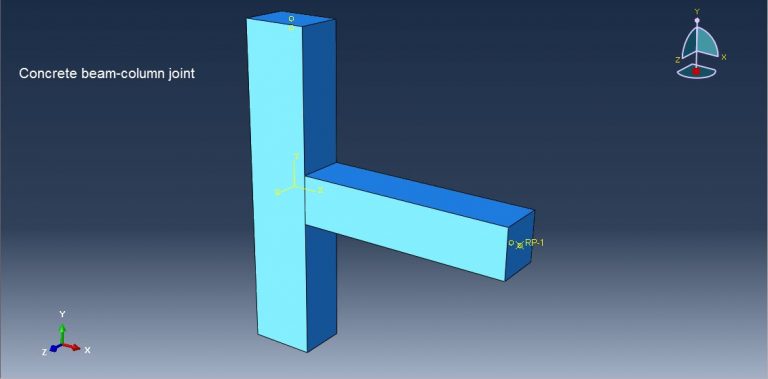

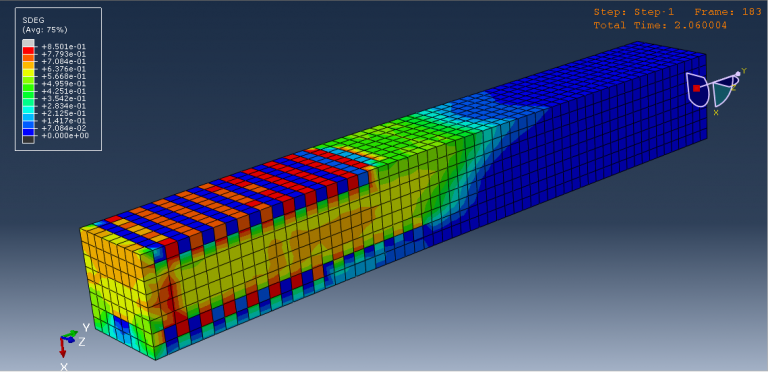

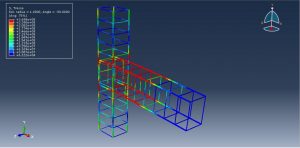

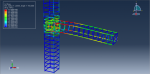

This workshop explores the simulation of concrete beam-column joints under cyclic loading with damage analysis in Abaqus. The beam-column joint is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, while the steel strips and bars are represented as three-dimensional wire parts.

The steel reinforcement follows an elastic-plastic material model, while the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model is applied to account for tensile damage in concrete during cyclic loading. This continuum, plasticity-based damage model considers two primary failure mechanisms: tensile cracking and compressive crushing. The uniaxial tensile and compressive behavior of concrete is defined within this framework, allowing for accurate damage representation. The primary objective of this simulation is to evaluate the concrete damage parameter under cyclic loading.

For this analysis, a general static step is selected. The embedded constraint is used to ensure proper interaction between the steel strips and bars within the concrete host. Fixed boundary conditions are applied at both ends of the column, while displacement-controlled loading with an amplitude function is applied at the beam ends following a cyclic loading protocol. A fine mesh is required to achieve accurate results.

Upon completion of the simulation, key results such as tensile damage, compressive damage, stress, and strain distribution are obtained.

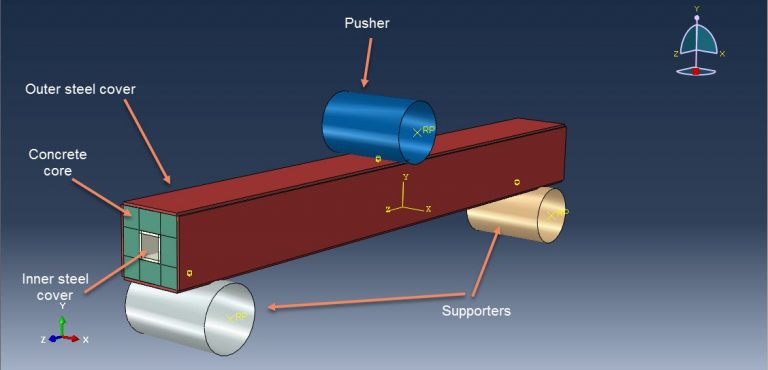

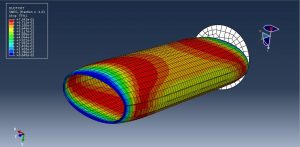

This workshop explores the simulation of an elliptical ultra-high-performance concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) column under compression loading in Abaqus. Elliptical CFST columns have gained significant attention due to their enhanced strength and stiffness compared to empty elliptical hollow sections. The UHPC core is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, while the steel tube is represented as a three-dimensional shell.

CFST columns are widely used in buildings, bridges, transmission towers, and offshore structures because of their high strength, stiffness, ductility, and energy absorption capacity. These composite columns consist of circular or rectangular steel tubes filled with concrete, and the elliptical CFST column is a more recent variation where concrete is filled into an elliptical steel tube.

To model the UHPC core, the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model is used, with material properties obtained from reference studies. The steel tube follows an elastic-plastic material model, incorporating a ductile damage criterion. The simulation is performed using a general static step with modifications to improve convergence.

A perfect or ideal contact is assumed between the steel tube and the concrete core, and general contact with frictional properties is applied to all interacting components. The bottom rigid body is fixed, while displacement with an amplitude function is applied to the top rigid body to simulate compression. A fine mesh is essential for achieving accurate results.

After completing the analysis, results such as stress, strain, damage progression, and the force-displacement diagram are available.

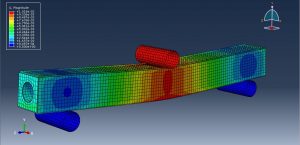

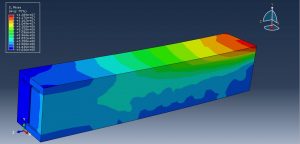

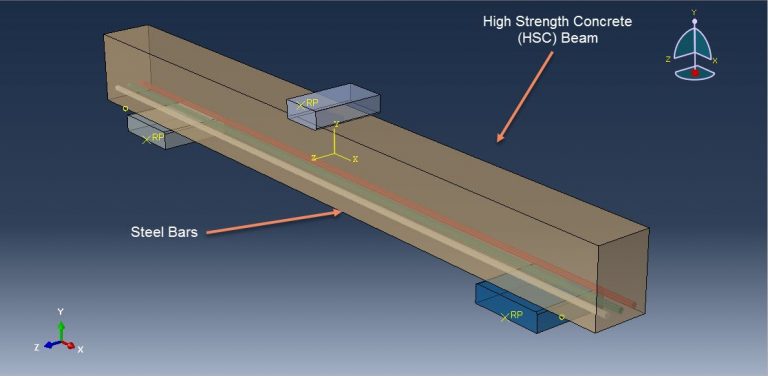

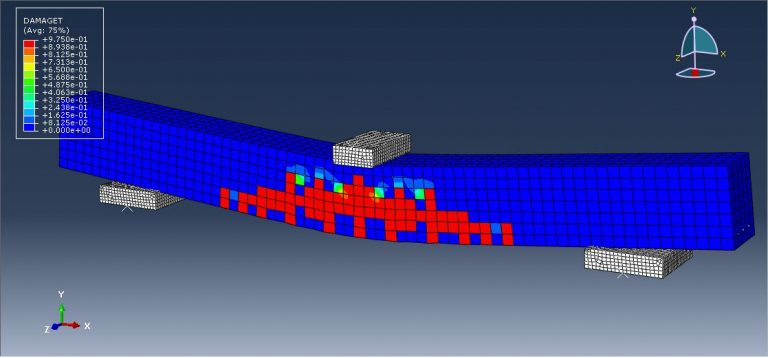

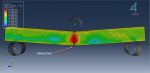

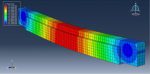

This workshop explores the simulation of a three-point bending test on a High Strength Concrete (HSC) beam in Abaqus. The key distinction between high-strength concrete and normal-strength concrete lies in their compressive strength, which measures the concrete’s ability to withstand applied pressure. While there is no clear threshold between the two, high-strength concrete is manufactured by optimizing the materials that make up normal-strength concrete. Producers adjust factors such as cement quality, aggregate selection, and the proportions of cement, water, aggregates, and admixtures to achieve the desired strength. The HSC beam is modeled as a three-dimensional solid part, and the steel reinforcement is modeled as a three-dimensional wire part.

The nonlinear behavior of concrete is modeled using the built-in Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) model in Abaqus. Four key input parameters are required to fully define the yield surface and flow rule in the three-dimensional stress space: dilation angle (ψ), plastic flow potential eccentricity (є), the ratio of biaxial strength to uniaxial strength (σbo/σco), and the shape factor (Kc), which defines the yield surface in the deviatoric plane. CDP data for HSC is extracted from reference literature. The steel bars are modeled with elastic-plastic behavior. A general static step with adjustments to the convergence model is used.

Surface-to-surface interaction with a friction coefficient is applied between the HSC beam and the rigid bodies. The bars are embedded within the HSC beam, and fixed boundary conditions are applied at the bottom of the beam. A displacement with amplitude is applied to the top rigid body. A fine mesh is necessary to achieve accurate results.

After running the simulation, results such as stress, strain, tensile damage, and the force-displacement diagram are available.

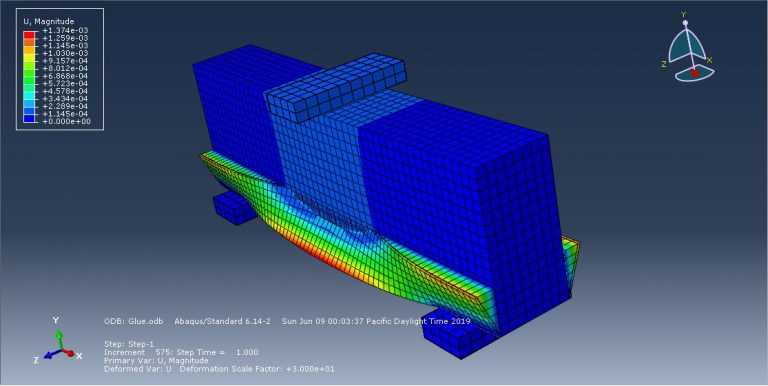

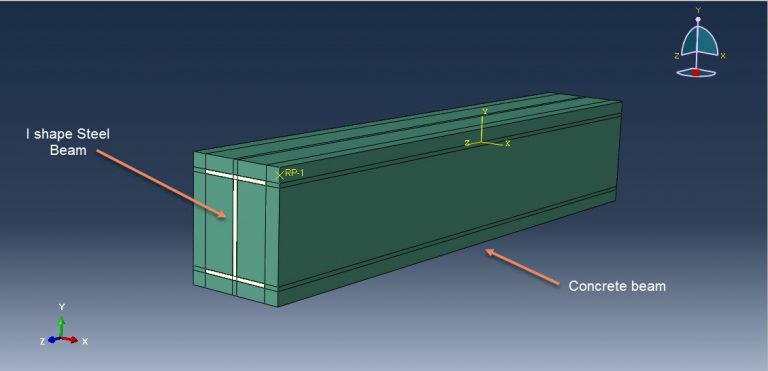

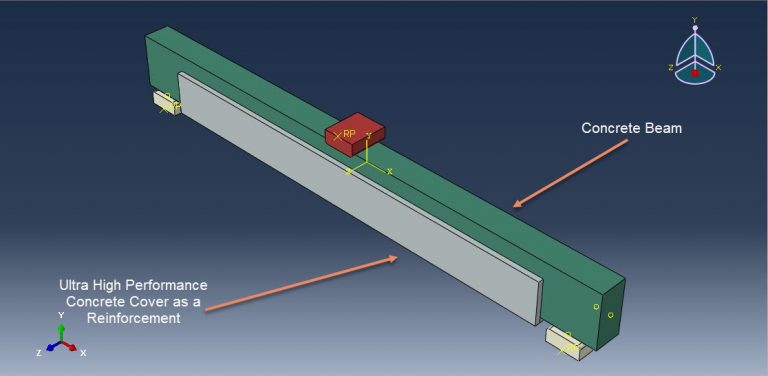

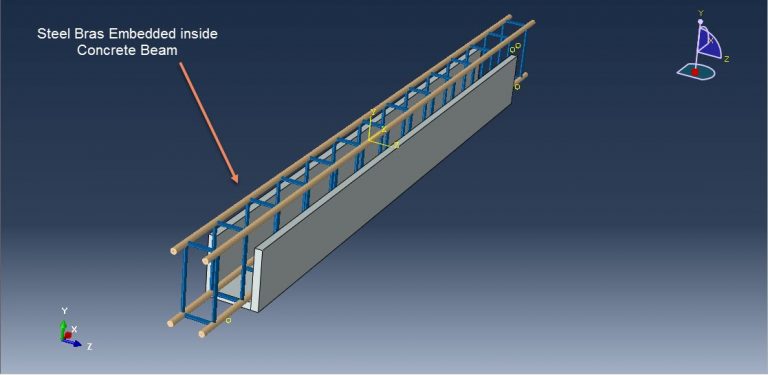

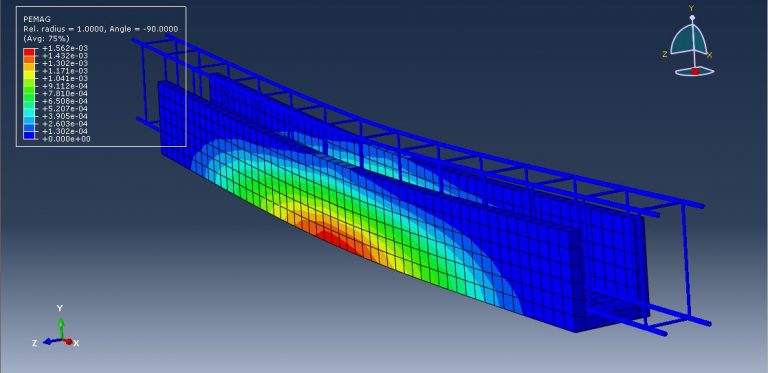

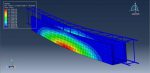

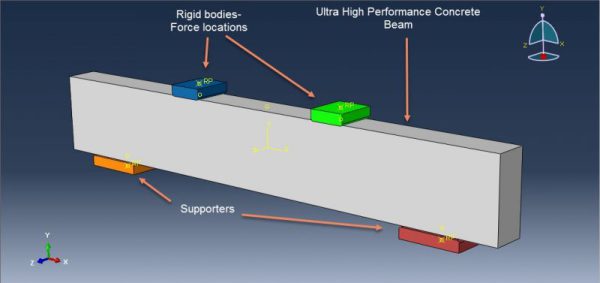

In this workshop, the simulation of the flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) in Abaqus has been conducted. Strengthening concrete structures is crucial not only for deteriorating structures but also for enhancing the performance of new concrete members under service conditions. This process is particularly important for critical infrastructures like power stations, nuclear plants, and marine structures, where demolition is often economically and technically unfeasible unless strengthening techniques fail to meet performance requirements. Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPFRC) has emerged as a modern material used for repairing and strengthening reinforced concrete (RC) structures. The concrete beam and UHPC cover are modeled as three-dimensional solid parts, while the bars and strips are modeled as three-dimensional wire parts.

The Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model is used for simulating the behavior of the concrete beam. This is a continuum, plasticity-based damage model that accounts for tensile cracking and compressive crushing as the primary failure mechanisms of concrete. The steel material for the strips and bars is modeled using elastic-plastic behavior, while the UHPC cover uses the CDP plasticity model, with material data taken from reference studies. The simulation uses a general static step, with modifications to the convergence model.

Surface-to-surface contact with friction is applied between the concrete beam and the rigid bodies. The bars and strips are embedded within the concrete matrix. Fixed boundary conditions are applied at the bottom of the beam, with displacement applied to the top rigid body using a smooth amplitude. A fine mesh is recommended to achieve accurate results.

After the simulation, results such as stress, strain, tensile and compression damage, and displacement are available.

Théo –

After using this course, my ability to solve real-world problems related to concrete structures improved significantly. The practical exercises and real-world examples in this course were very useful.

Otávio –

The content of this course is very comprehensive and complete. All the relevant topics related to concrete modeling in Abaqus are covered.

Leônidas –

This course helped me reach a higher level of proficiency in Abaqus. After completing this course, my self-confidence in tackling concrete projects increased significantly.

Caetano –

After using this course, I was able to quickly create and analyze more sophisticated models in Abaqus. The tips and tricks presented in this course were truly effective.

Henrique –

The quality of the videos and explanations provided in this course is excellent. The instructor was able to effectively communicate the complexities of concrete modeling in simple and understandable terms.

Taís –

The content of this course is up-to-date and practical. For example, the sections on UHPFRC and CFRP modeling were very helpful and aligned with the latest research and industry practices. What would your recommendation be for those who are looking to learn concrete structure modeling in Abaqus?